Raising Hell: Issue 80: A Loss Of Trust In Management

"The truth is, through all these years of public service, the 'service' part has always come easier to me than the 'public' part." - Hillary Clinton, 29 July 2016.

Back in November 2023, right as I was preparing to jet off to Dubai for COP28, I had a commission come through from Science magazine in the US. The brief was pretty straight forward: follow up a report that had appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald and see if I could learn anything more.

The story was a good one. A group of lawyers in the United States, representing people who had been affected by the Deepwater Horizon Oil, had found documents through discovery that they claimed showed BP had ghost written and ghost managed the production of nine papers CSIRO research papers. The team responsible for producing these paper worked with the agency’s oil and gas division.

I reported the story with what I could find at the time and I have kept on with it since as there were several questions. First: what happened here? Second: what level of influence did BP Legal actually have over the production of research? And third: why the hell was CSIRO being so cagey?

At the time of publication, CSIRO did not provide any clear explanation for what had happened. The lawyers over in the US had happily provided documents underlying their allegations; CSIRO had simply issued a denial and circulated a statement that their actions were consistent with the Australian Code for Responsible Conduct in Research 2018. If you checked the code, however, it contained the following advise on managing “institutional conflicts”:

“In accordance with the principle of transparency, institutions are encouraged to respond to reasonable requests about the sponsorship of research and how any related competing interests or conflicts of interest were managed.”

You might say it was something of a discrepancy.

Since that report went live, I have been using information to dig more into this story. I have made several applications to date — I won’t detail them in full right now, as it is too much, too technical and I don’t want to pre-empt any story that comes from this on-going project. In order to give a sense of what is happening, I do want to talk about the most recent application I received for the way it speaks to a much wider attitude among government departments more generally.

And to understand that, the first thing to understand is that the public service, as an institution hates Freedom of Information and has done so pretty much since its inception. The idea that the public has a right to go rifling through the personal letters, emails and draft documents of decision makers and those out there in the civil service is a source of endless frustration. So too is the way in which these right means individual public servants can be identified by name, rank and serial number.

It should probably come as no surprise that, as long as there has been a public service, the greatest fear among the leaders of this brotherhood is that they may have to actually engage with the public. If public servants are required to give frank and fearless advise to ministers and departmental heads, the thinking goes, FOI compromises their ability to do so by offering no protection against those who dissent. Even now this line of thinking is being used to explain Robodebt debt. The real problem behind the program that sought to rifle through the pockets of Australia’s poorest citizens, according to former Department of Finance and Department of Health head Jane Halton, was allowed to go ahead not because those in charge legitimately believed the average person on social security was a liar. Rather, the issue appears to have been too much transparency.

Halton told the ABC in July 2023:

“FOI has a chilling effect, I think, on people being very frank. The notion that everything might be available is something that people do think about quite carefully before they put things in writing. And that is a discussion that needs to happen.”

One expression of this has been the recurring skirmish across government agency’s to redact the names of individual public servants. For what it’s worth, each time this is challenged in court, the agency in question tends to lose.

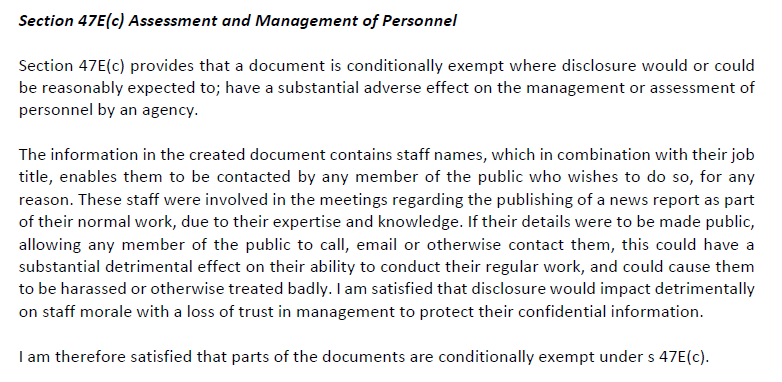

In this instance, the CSIRO has become the latest agency to attempt this over the course of our exchanges, dressed up over apparent concern for the safety of the agency’s staff. What has been interesting about this process so far is that, from the moment I began asking for the underlying documents, the agency appears to have treated these materials like they were state secrets. These applications were redirected to senior counsel, and this most recent application gives you the flavour of what these interactions have been like:

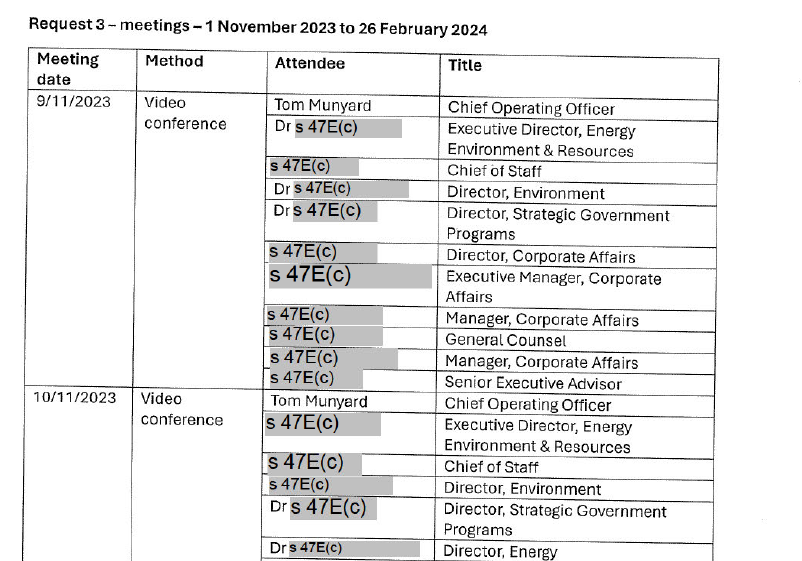

This, by the way, is how you end up with the disclosure of documents that contain a list of meetings and titles but no names:

It would be easy to look at the decision and take the reasoning at face value. There are anti-vaxx0rs out there storming council chambers, guys blowing up 5G towers and political figures like Coalition Senator Gerard Rennick and One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts who seem to believe that, with the power of their singular mind(s), they have unpicked the science of climate change. What is worth keeping in mind however, is that the documents I asked for were copies of meetings by an executive-level group within the agency who met regularly around the time I was doing my reporting to respond to the allegations published in The Sydney Morning Herald. I also happen to know, from my previous applications, that the purpose of this group was to coordinate a response that included trying to head off my attempts to report out what happened here.

The reasons why they might do this are obvious: serious allegations have been made that need to be responded to and managed. What is portrayed, however, as a singular focus on the wellbeing of staff, however, does not include the potential for a black eye for the organisation if any of the nine papers in question are retracted due to misconduct — or the flow-on effect it may have for the agency’s attempts to court new business.

These, however, are all irrelevant factors in weighing up whether to grant access to the documents — decision makers are not allowed to consider the potential for embarrassment by agency when making a decision. These pesky rules, however, do not stop an agency for attempting to use procedure to frustrate the application by issuing bad decisions that necessitate appeals which will in turn take several months, if not years, to work through.

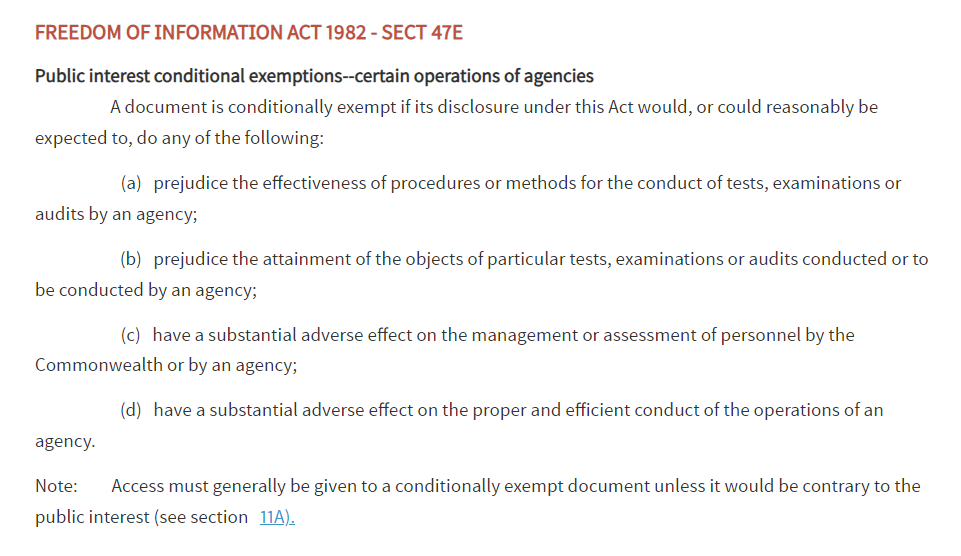

Case in point: if you actually go and look look up s47E(c), for example, you will find that the specific sub-section has nothing to do with the personal safety or morale of the personal, but rather the “management and assessment of personnel”:

What is also curious is the way in which the decision appears to equate being identifiable and possibly contactable with a probable risk of harassment. A generation of Millennials, and now Zoomers, have suffered as their elders moan about how they’re too afraid to pick up the phone and talk to someone directly. As it turns out, it’s Gen-X public servants who seem to believe that the mere possibility of being contacted by someone, however remote, constitutes an act of harassment.

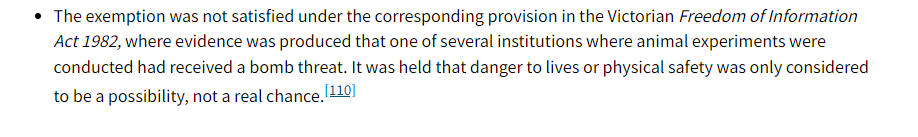

Jokes aside, it is plain the agency appears to be implying some concern about the possibility it may been subjected to protest from groups like Extinction Rebellion who might take issue with its ongoing work for oil and gas companies — and especially company’s like BP who are still being sued for their role in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and would very much like to wriggle out of legal responsibility. Unfortunately, even here, the law is not the agency’s side. There is a difference between feeling safe — a subjective evaluation — and being actually safe — a clear measure of material circumstances. One case cited in the FOI Guidelines, as an example to help define what constitutes a “real and substantial” risk of harm, involved a Victorian government agency which refused to disclose a list of institutions where animal experiments were being carried out, citing a bomb threat it had once received. The court found that a possible risk of danger was not a probable risk of danger:

If even a bomb threat made against several random institutions was not enough to prevent disclosure of the document, I’m not entirely certain a court would agree that the terror CSIRO staff might feel upon being contacted by a third party, let alone a bad faith actor, is silly.

And in saying all this, it’s worth remembering the possibility that the agency has done nothing wrong at all — though so far the agency’s actions suggest this is the case. In refusing to answer direct questions, fighting every single attempt to learn more information — including refusing to provide draft copies of the nine papers in question — the agency has provided no alternative explanation, or any evidence to clarify its relationship to BP on this project. Arguably, if the agency had been straight up in responding to the allegations, the risk to its staff may have even been minimised. But by fighting so hard to jam up all lines of enquiry the agency has suggested, by its actions, that there is a probable story here — we just don’t know it yet.

For the period of 8 May to 21 May…

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

It’s mostly been back-of-house this fortnight, though I do have one story coming in The Guardian this week, so keep an eye out.

You can also check out the sweet rebuild I did on my personal website - photo courtesy of Isabella Moore. You can also check out the website for SLICK if you haven’t already — and check back because it will be updated with key information up to and following publication.

I also want to take some time to note the announcement by the Walkley Foundation not to renew its partnership with Ampol. For years, Ampol has been a financial partner of the Walkley Awards, Australia’s equivalent to the Pulitzer, but the relationship between the fossil fuel retailer and the media has been increasingly called into question. In more recent times, the organisation has reportedly taken to not displaying the Ampol logo during the awards ceremony as people in the crowd booed. The awards have also faced a campaign, led by the nation’s cartoonists’ who have been refusing to enter their work.

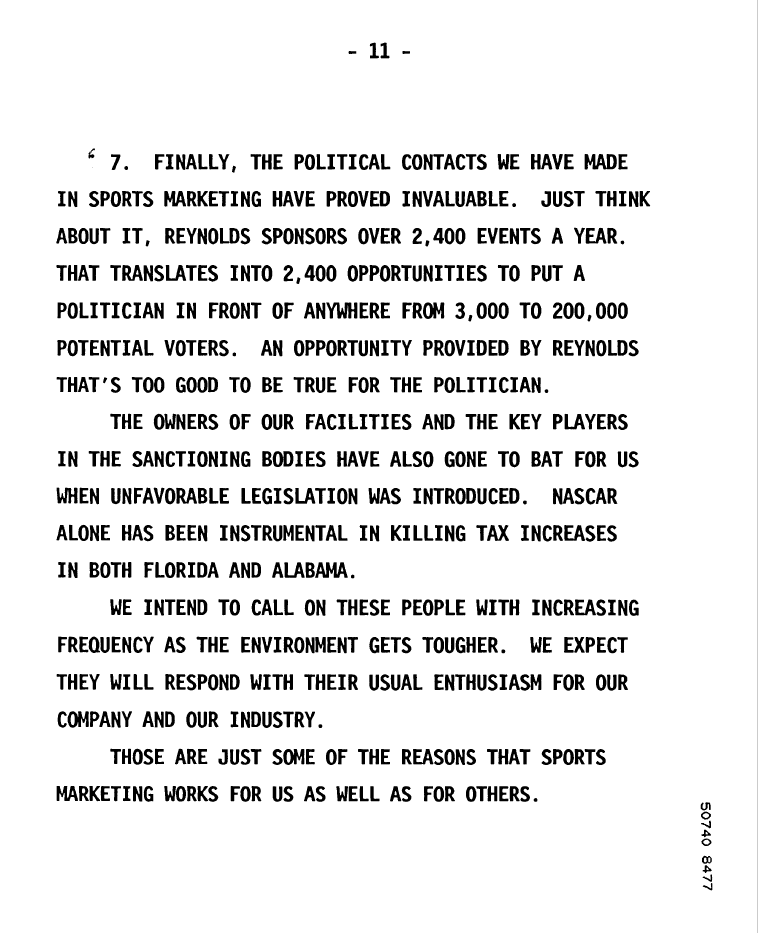

I, similarly, withdrew my entry in this year’s Mid Year Awards for the category of Best Science and Environment coverage, citing my previous and ongoing reporting of fossil fuel sponsorship of art, sport, education and community organisations. The decision to end this association — after seven decades — is a good one and very welcome, despite the grumbles of a few stray business reporters. And speaking of the objections from these lone voices, I always think it is worth pointing these objectors to speaking notes found in the tobacco archives. These outline, clearly, how industry players keenly understand their role in sponsoring sport (and by extension the arts) helps to advance their political goals. The same could easily be said about fossil fuel companies and the media whose role it is to cover them.

Before You Go (Go)…

- Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

- And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!