Raising Hell: Issue 82: We Encourage You To Seek Support

"That’s the trouble with accountability sinks. They store negative feedback, but don’t deal with it." - Dan Davies, author of The Unaccountability Machine, in The Financial Times, 14 June 2024

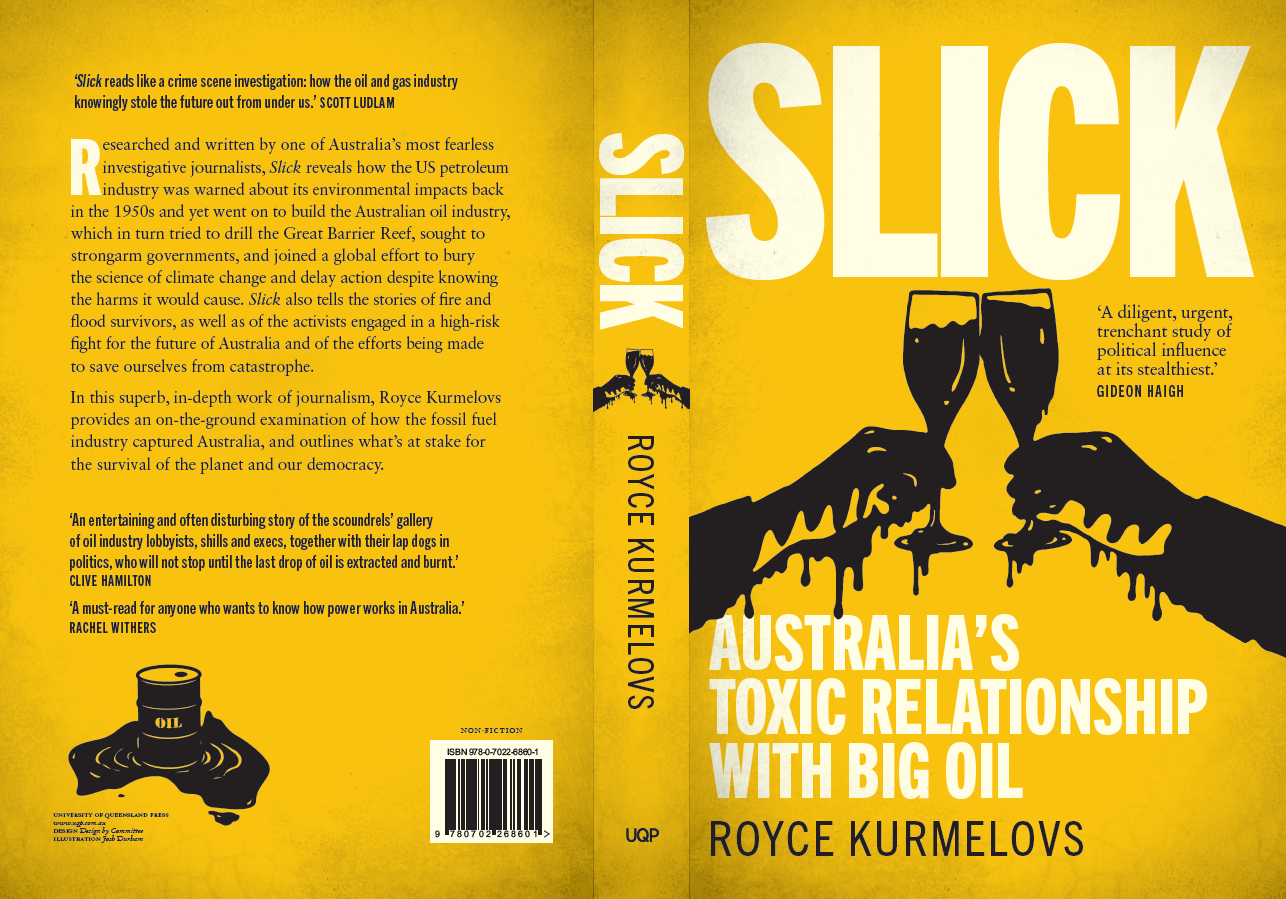

Under normal circumstances I would kick off this newsletter with a bit of scene setting that allows me to talk about the latest project I’ve been working on. I have, I should say, spent most of this last fortnight working on a fun longread about “How Fossil Fuel Companies Taught Australian’s To Love Gas” that I filed on Monday. The completion of this story owes much to the financial support of Raising Hell’s paying subscribers, whose contribution helped cover for the visit to two archives in Sydney and Canberra to engage in the necessary research. This story, for what it’s worth, will be the second to come out of that trip — the first being the report on Apartheid South Africa I found in William Walkley’s personal papers which provides an insight into the racial politics of Australian media’s patron saint. If you want a recap of some of what I found, you can go back and check out some of the primary materials, which I talked about in Issue 81.

But circumstance means I’ll be putting this off until a little later to address something more pressing: the decision by the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) to not pursue an investigation against six public servants over their role in creating, facilitating and then covering up the Robodebt scandal, and the subsequent decision by NACC Inspector Gail Furness to investigate the decision not to proceed.

As you may imagine, I have thoughts.

When news first broke about the decision not to investigate, I was not surprised. Anyone who had been following events and listening to the activists in this space could see the general arc of where things were headed. Catherine Holmes’ Robodebt Royal Commission report — a landmark moment that vindicated and validated all the allegations levelled at those involved — had barely been handed over before the campaign to blunt its impact got underway. NACC’s decision felt like more of the same — for more on the specifics of what this means, see Christopher Knaus in The Guardian.

Mostly, my position can be summarised simply: I think it’s just plain embarrassing and illustrative of a centre-left political leadership with a wonderful capacity for self-harm. But as much as Chris sums up my thinking, I also believe this is a moment that helpfully illustrates a few abstract ideas about accountability and transparency that are worth drawing out.

The first is something Justin P Warren, who is still fighting in the courts for transparency around Robodebt, has previously been at pains to remind people: the purpose of a system is what it does. If the purpose of Robodebt was to shake down the poor for change, NACC’s purpose, it seems so far, is to not investigate things that concern poor people.

The second is that, to get to this point, a string of political, legislative and communications decisions had to be made. The cumulative effect of these decisions — all made by separate people acting independent — was to create a set of nested “accountability sinks” which we are now seeing in action. The accountability sink is a metaphor created by former Bank of England regulator Dan Davis, author of Lying for Money and The Unaccountability Machine where the basic premise is simple enough: there are people who decide things, and there are those who have decisions made about them. An accountability sink describes any institutional set up that works like a septic tank by drawing nasty negative feedback away from decision makers and into another, isolated part of the system. Some accountability sinks have valid purposes — like the system of precedent used in the judicial system to give a sense of order and method to individual judgments. Often, however, these arrangements are created to allow powerful people to play an Uno-Reverse card on victimhood. If those with decision making power and agency can claim they are actually powerless to give an alternative decision, than those seeking to hold them responsible for their decision are actually nasty, mean-spirited bullies. What other choice did they have?

Accountability sinks are one of those concepts that, once you start looking for them, you start to find everywhere. What is important to remember about both accountability sinks and septic tanks, is that as Davis himself has pointed out, if left unattended, they will eventually overflow with unpleasant consequences for everyone involved.

Robobdebt, in many ways, was archetypical. It was a system designed explicitly to reach into the pockets of Australia’s poorest citizens and then, if they complained, point them to a sign in ten-foot-tall neon that read “because the computer says so”. It is also an example of an accountability sink that became unsustainable under the sheer weight of its own operation. Eventually enough public rage accrued that it inspired a whole movement that helped seed the social conditions necessary to bring down its creators.

As a Moral Crumple Zone, NACC may be thought of as a slightly more advanced accountability sink. Think of it similar to software installed in self-driving cars that automatically returns control of the vehicle to a human driver moments before it kills a pedestrian, thereby allowing the carmaker to claim in court they weren’t legally liable. A look at the body’s public statement makes the comparison, in some ways, uncanny. It contains all the usual lip-service to “the recipients of government payments or their families who suffered due to the Robodebt Scheme”, even as it attempts to explain how it is utterly powerless to proceed. NACC “cannot grant a remedy or impose a sanction”, it claims before adding: “an investigation by the Commission would not provide any individual remedy or redress for the recipients of government payments or their families who suffered due to the Robodebt Scheme.”

These sorts of statements may have come as a shock to someone like former Chief Justice of the Queensland Supreme Court Catherine Holmes, who seemed to believe otherwise. Unlike NACC, her role in the Royal Commission was genuinely limited to fact finding. She had no power to determine whether someone was “corrupt”, which would in turn allow members of the public to call those individuals corrupt without risk of a lawsuit. All she could do was set out the facts as she found them. To go any further required a separate organisation the rough size, shape and mould as a National Anti-Corruption Commission.

This was why Holmes had delayed the delivery of her final report to allow for the creation of the body, and then delivered the newly created institution a sealed section that outlined the case against six senior public servants to avoid prejudicing any criminal case that may be brought against them. When the unnamed deputy-commissioner who had been delegated the responsibly for making the decision whether to proceed or not, likely owning to Paul Brereton’s pre-existing relationship to Brigadier Kathryn Campbell, actually reviewed this material, they appear to have been impressed by the thoroughness of Commissioner Holmes’ fine work — so impressed, they declared the job was done.

“In the absence of a real likelihood of a further investigation producing significant new evidence, it is undesirable for a number of reasons to conduct multiple investigations into the same matter,” it said. “This includes the risk of inconsistent outcomes, and the oppression involved in subjecting individuals to repeated investigations.”

A failure to investigate, however, means the material outlined in Holmes’ sealed report will remain off-limits to the public, but one of the concerns at the NACC was the potential for any investigation it might carry out would necessitate “duplicating work that has been or is being done by others”. Instead, it suggested other bodies like the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) were better positioned to investigate something like Robodebt. Better to focus on “lessons learned”, it said.

Whether or not APSC could actually, meaningfully pursue and sanction those public servants who retired either remains to be seen — but the NACC was not done. Aware that the impact was coming, the institution braced itself. The social media post that carried its statement to the public further advised readers that: “we understand that our decision not to pursue the referrals from the Robodebt Royal Commission will be difficult for victims, their families and friends.” The same post linked out to a page on NACC’s website that included a series of links to support services, first among which was Lifeline, the suicide crisis-help hotline. Comments on the post were turned off.

In other words: don’t kill yourself, but we’re powerless to help you. Also, don’t yell at us.

There is no good way to deliver bad news but as an exercise in public communications, this was a disaster. Message received, all that public anger which had built up found itself without an outlet and so focussed entirely on the NACC — even I, for my sins, indulged in some largely baseless speculation on social media about the timing of the announcement, born of a deep cynicism earned during the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison era. The sheer tidal wave of anger that prompted the NACC inspector to intervene it itself interesting. Thinking about it from an institutional perspective, the inspector functions as a pressure release valve to protect the legitimacy of the overall institutions.

So with the government of the day pointing to the NACC, the NACC pointed to other investigative bodies which may or may not deliver a resolution, and the institutional set up now kicking in to head off a crisis of legitimacy, what we have is a total mess —but also clarity about the failure, or refusal, of those with power and influence to grasp the lesson of Robodebt.

First the public watched as powerful people built an system that took money from the poorest Australians with no avenue for them to challenge the decision, and now they are watching as powerful people repeatedly throw up their hands in defeat and claim to have no power to impose any kind of meaningful consequence. Sure, Robodebt may have killed people but figures within the public service have lobbied against reforms to open the black box, and the bizarre decision has been taken to reward those involved with $900k salaries to advise on very non-public aspects of the AUKUS program. All this reinforces a very basic message: consequences are for poor people.

Framed this way, is it really a mystery about why people are so mad?

For the period of 5 June to 18 May…

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

- ‘Heat pumps: how to reduce your carbon footprint while saving money this winter’ (online, Guardian AU, 8 June).

- ‘I need your help saving koalas’: how Australians banded together to build wildlife corridors’ (online, Guardian, 13 June).

Before You Go (Go)…

- Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

- And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!