Raising Hell: Issue 92: A World To Win

"When an absolute decision is obtained the system of the victors — whoever they are — will probably be adopted to a very great extent by the vanquished." - Winston Churchill, 9 July 1916.

Not too long ago I was invited to participate in a panel discussion at a local community event talking about climate change. Not only was I from out of town and new to this community, I was one of several people invited to speak — people who had way more salient things to add than I did. But at the end of the day, I had a book to sell, and so self-interest won out.

After the talk, questions followed. One of those who stood to ask a question was an older woman who look like every other woman who might inhabit a vaguely regional area. All the ra-ra talk was all well and good, she said, and the problems we diagnosed were concerning, but what should she and others actually do about it?

It was a good question — one that I usually don’t feel qualified to answer. As a working journalist, I am not a legislator, a political strategist or a campaigner. My job is to find things and make sure people know about it. Moving from is to ought was always uncomfortable territory.

Neither did it help that the quick answer felt so unsatisfying: break the hydrocarbon chain — install solar panels and batteries; convert to electric vehicles; electrify home and garden appliances; stop flying as much; take public transport. These were all good, clear steps a person could take to address the issue, but they were also divorced from context like telling someone living in poverty to just budget better. Taking action took money and often people had none. A person’s mortgage might be too large, or their work paid too little. Those living in an apartment complex were at the mercy of their landlord, as were those living on social security who could barely afford to eat, let alone chose where to live. The thing with individual solutions is that even when they are the right choices, they can often feel like staking a claim to the highest seat on a sinking boat when the moment demands everyone get busy helping to bail.

If we are to think about climate change not just as a class issue, but as the class issue, it is possible to get a little more clarity when it comes to answering this sort of problem. Decarbonising the home and the workplace are both essential goals to dealing with climate change, but how we get there requires something more. If there isn’t money to achieve these things, for example, the situation demands some mechanism for finding that money or demanding it be made available.

It also requires a strong understanding for the kind of change taking place in the macro and where things might be headed. For that, it helps to draw a little inspiration from Michal Kalecki, a man who saw the end of his era coming before it even began. Kalecki was a economist had been born to a Jewish family in 1899 that had assimilated into Polish society. He would come of age in the turbulent years leading up until 1935 when the reality of the situation in Europe was becoming undeniable and, in the first exercise of the foresight that would characterise, Kalecki sought to escape his situation by finding a teaching position in the United Kingdom.

It was perhaps his early encounters with class conflict, violence and ethnic hatred, combined with his training in economics, that gave Kalecki his incredible insight — a trait he would demonstrate when he published a six-page article in 1943 that predicted the broad direction of politics across much of the developed world for the next four decades.

Titled, “The Political Aspects of Full Employment”, the article concisely sketched out the class dynamics that would make and remake the world. At first, Kalecki said, the end of the war create a worker’s paradise which would later be undone. Though he never expressed it in such naked terms, Kalecki understood even before the end of the war that a generation of traumatised young men with firearms training and a working appreciation for small unit tactics made for a dangerous moment. To keep the peace, political leaders converged upon a simple solution: keep ‘em busy. In this post-war world, the primary goal of public policy would be to ensure full employment, or conversely zero unemployment, meaning everything a government did was viewed through this prism. In effect, every law, administrative decision, policy decision or regulation would be considered against what was needed to keep these men in a job, their family in a home, and their children healthy.

The result was a society more equal in terms of wealth distribution than anything the Soviet Union achieved but one Kalecki understood was always on borrowed time. This was based on a very crucial insight: any particular institutional arrangement created to respond to a specific problem will eventually solve that problem, and go on to generate contradictions that, by its very operation, will undermine the reason for it continuing to exist.

In other words: good things never last.

In Kalecki’s case his basic insight was eternal. The wealthy might be rich, but they wanted to be richer and so they would vote with their wallet in front of mind. Their moment would come with the dawn of the 1980s and the counterrevolution of Thatcher, Reagan and Keating. When this time came, an inversion took place just as Kalecki predicted. In the midst of an inflation crisis, work became irrelevant and suddenly the price of eggs mattered most. With zero unemployment out, zero inflation became the primary goal of public policy and every action of government came to be measured against how it might keep prices low. Unions were broken or marginalised, cheap and easy credit was everywhere, governments were kept at arms length from everything and money was free to hopscotch across borders at will. The rich got so much richer.

Much of my work to date — over the course of three books, The Death of Holden, Boom and Bust, and Just Money — has been about examining what happened next as this system, too, blew up in 2008. Like the post-War Period, the world of the neoliberal 1980s solved for inflation and then devolved into a mess of contradictions that eventually collapsed with the US housing market, taking the global economy with it.

This time around, however, there was no Michael Kalecki to offer a way out. Instead, populations around the world watched as for nearly two decades political leaders stumbled around in the dark trying to do more of the same. There was already a challenge brewing to the political order, one I wrote about in Rogue Nation that prefigured the rise of the Independents movement, when the Covid-19 pandemic struck in 2019. At that moment people who had spent a lifetime being told the government could do nothing for them, watched as government suddenly moved. In Australia, at least, income guarantees were made, social security was hiked, evictions were frozen and vaccines were made free. A friend of mine, a financial counsellor then working in Elizabeth, South Australia, reported at the time he was no longer seeing his usual clients as the those struggling to budget their way out of poverty could suddenly afford food. Almost overnight, he said, the people coming in through his door were middle-income and struggling to service their mortgage.

In many ways this was a better time for many people, even if panicked governments leaned heavily on the police to enforce their pandemic-restrictions. In the scheme of things, this was exactly the moment that offered the opportunity for a profound shift in thinking. Across the board centre-left parties in the United States, the UK and Australia rose to the occasion by promising a “return to normal”. It was a pitch that relied on an incomplete read of the situation. It worked until it didn’t.

Though this centre-left governments tried their hands at an ambitious reform agenda — the Inflation Reduction Act and similar policies across the UK and Australia — it wasn’t enough. These were good ideas in principle in but on balance tended to focus on creating “good incentives” and handing big sums to large corporates. Any effort to directly boost living standards came to late or just wasn’t prioritised.

This brings us to the present as, into this vacuum of ideas, Donald J Trump has stepped the second time. Having been returned to the White House he brings with him a government of crooks and oligarchs shilling an incoherent nationalist-libertarian hodgepodge ideology opportunistically blending anti-war sentiment, tariffs, locked borders, low taxes, greater fossil fuel extraction and no environmental controls — or regulation of any kind.

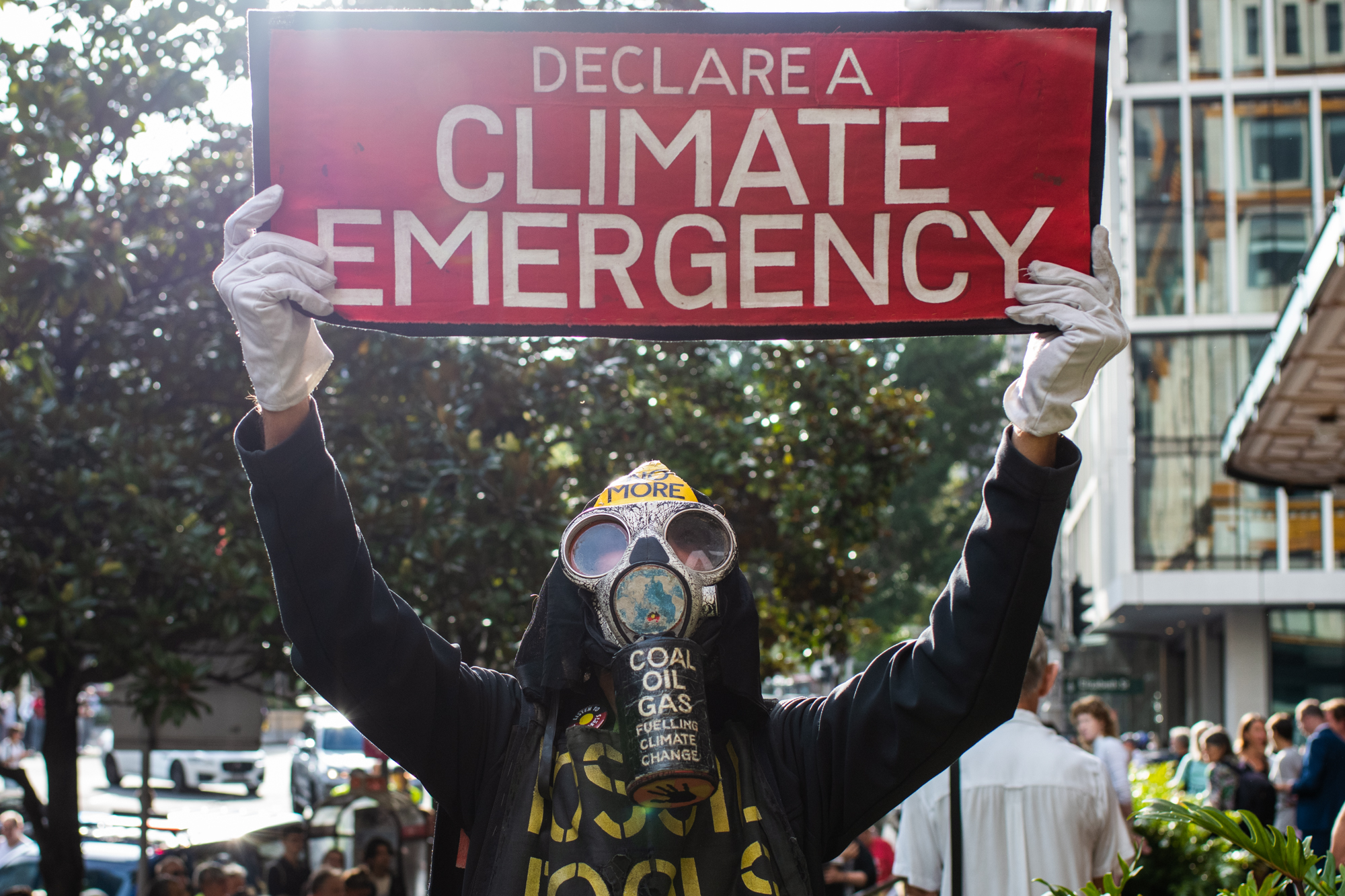

Even as the Australian right wing make the same kind of pitch, the irony is that there was always an alternative waiting in the wings: zero carbon. If the post-war era focussed on zero unemployment, and the neoliberal era prioritised zero-inflation, the pressing, existential threat of climate change demanded a response — one that required all public institutions pulling in the same direction. In the same way every law passed, and every executive decision, was made in the context of securing full employment or stopping inflation from rising out of control in their respective periods, every act of policy should, arguably, be now considered against how it might achieve this goal.

This is also what people were driving towards when the call went out for a mass mobilisation to deal with climate change, or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez co-published her plans the Green New Deal in the US — both suggestions that have had a decidedly cool reception in Australia. When I tried to interview Australian political leaders about it at the time, there was a real disinterest in talking about it. With The New Deal a plot point in the storied canon of American political history, it did not exactly resonate with Australians at the time. Worse, the “green” branding made a political leadership more concerned about marketing than material conditions uncomfortable. If Labor Red and Liberal Blue signalled allegiance, a Australian Green New Deal was perhaps ceding a little too much to the “Greens political party”.

At heart, the core idea behind these proposals remains powerful — that climate change cannot be separated from questions of equity and social justice. Approaching this as a class issue doesn’t just diagnose the problem, but helps point in the direction of real, material actions. At a minimum, the physical work required to deal with climate change in an equitable and just way requires upgrading the electricity system; swapping out every car on Australian roads; building trains; ensuring everyone has clean drinking water; retrofitting every machine that runs in external temperatures to operate in higher heat; insulating every home; electrifying households; upgrading building codes; rethinking how we build neighbourhoods and cities to respond to a hotter, more disaster-prone climate; reworking agricultural practices; helping workers leave the carbon-economy for the clean economy as the old refineries, rigs and mines close down; raising social security to the poverty to catch people when they fall; ensuring enough protections at work so people aren’t forced to work in dangerous conditions; cutting to public and private financing for new fossil fuel infrastructure; subsidies and support for electrification particularly in regional areas and remote Indigenous communities; the accelerated installation of renewable energy; strong regulation to ensure these efforts are carried out; overriding legal precedent that neutralises a push for action…

The list goes on and when laid out like this it seems overwhelming, but it also promises something important: work. A bunch of it. Not only does this require the training, physical labour and manufacturing capacity to make happen, it requires commitment and the organisational muscle to demand these changes when they aren’t happening. Yes, this does involve voting wisely or at least defensively, getting people elected and writing policy submissions — but that is not all. If people don’t have the funds to change, that is a political issue that needs work. If your school, university, sports club, art institution or church group takes funding from fossil fuel industry, the experience elsewhere has been that divestment and disassociation campaigns work to isolate lobbyists and their their voice mute. Regions prone to fire or flood might organise emergency response committees who can coordinate evacuations and material support when the rain won’t stop falling, the smoke clogs your lungs, or you need someone to cool off on a hot day because your landlord won’t shell out for air conditioning. Indigenous communities, whose communities are often on the frontline of fossil fuel expansion, cannot respond when harassed by police or locked out of their country.

And the good news is that there are already a wealth of organisations out there who are doing this work. There are unions working to help their members escape the carbon economy (and some that are working to maintain it), student groups investigating their university finances, housing groups thinking about how to provide shelter during heat waves or emergencies, community groups thinking about how to help people evacuate, architects working on building better cities, regional communities investing in battery or renewable energy projects, people resisting the anti-renewables moral panics that are being spread, anti-poverty groups working with those struggling to survive on social security — and hundreds of others. Sometimes, taking action can be as simple as cooing a meal or giving someone a lift — the first step is to look around to see what is going on in your community and asking to help out. No organisation is perfect, but chipping in is a start.

The advantage of thinking about climate change as a class issue is that it suggests certain short and long-term goals. It is tangible, material — something that becomes possible to grab onto rather than staring into the abyss. Something that offers hope. There is a world to win — and a lot of work to be done.

Good Reads

Because we here at Raising Hell know how much you love homework…

- Tim Baxter has a detailed write up of the Gorgon carbon, capture and storage facility in Western Australia that methodically examines how it failed to live up to the hype.

- Derek Guy the men’s wear guy also penned an interesting BlueSky thread talking about what makes Japanese culture so interesting — and, spoiler, it has nothing to do with racial essentialism.

- Alison Rose Reed has a great write up of her view of American society from inside a strip club over at her Substack with a great essay titled: “I’m a Stripper; Of Course I’m Not Surprised by Trump 2.0”

"Many books about climate change are worthy but dull. Slick, however, is as readable as it is shocking." - Richard Denniss, The Australia Institute, writing in The Conversation.

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

- ‘The Australian Public Servant Who Helped The Oil Industry Convince The World That Stopping Climate Change Was Too Expensive' (Drilled, 22 November 2024).

- ‘Revealed: Oil Majors Used A Little-Known UN-Affiliated Organization to Seed the Economic Argument Against Climate Action’ (Drilled, November 21 2024).

- ‘The Great COP Co-opting: New Documents Show Big Oil Has Been There All Along’ (Drilled, 20 November 2024)

- ‘Woodside handed government funds for carbon capture projects, but activists say we should use less gas’ (Renew Economy, 21 November 2024).

- ‘Labor issues new mandate to Future Fund to invest in the future, and the zero carbon economy’ (Renew Economy, 21 November 2024).

- ‘Australian homes could slash energy bills by two thirds by cutting out gas and petrol, AEMC say’ (Renew Economy, 29 November 2024).

- ‘CSIRO hails successful road test of lower-cost green hydrogen technology at steel plant’ (Renew Economy, 1 December 2024).

- ‘Australia is making mixed progress on emissions and rapid cuts are needed, says CCA’ (Renew Economy, 28 November 2024).

- ‘“Get out of the way”: Manufacturer wants more renewables to soft price crunch and avoid shutdowns’ (Renew Economy, 28 November 2024).

- In case you didn’t catch it — Slick was shortlisted for The 2024 Walkley Book Award, a development that deeply surprised and appealed to the hooligan in me. Parts of Slick, and much of my reporting, has been given over to investigating William Walkley’s track record (which ain’t pretty). Unfortunately, Slick didn’t win in the end with the prize going to Nuked.

Before You Go (Go)…

- Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

- And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!