Raising Hell: Expert Interview: So How Cooked Are We, Exactly?

"I owe the public nothing." - JP Morgan, American financier and banker, 11 May 1901

Back in July I watched events at a certain Senate finance and public administration references committee unfold with a sense of dread. Bigwigs from the country’s four largest insurers had got together in the same (virtual) place to tell the inquiry how despite ten years and thousands of warnings about climate change, they had done sweet nothing. More than that, when they looked at the course of events, the Masters of Risks were blunt in explaining they did not think there was a hope in hell that world governments would do anything about climate change — a statement particularly jarring given they were now feeling the heat. Everyone who contributed to that session openly acknowledged they were beginning to absorb the costs from a series of catastrophic weather events that were stronger and more frequent than any could recall.

As this group of finance guys sat around talking about the end of the world, I couldn’t help but recall how the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 only really kicked into high gear when the insurance companies began to go bust. Not being an expert on finance, I then began to wonder what others who knew about these things might think — someone like Associate Professor Michael Rafferty of RMIT University.

Mike was among the experts I turned to while researching Just Money to help me make the incomprehensible gibberish that is most financial reporting into something legible. So with news that the central financial organs of the modern Australian economy are in deep financial trouble — and getting deeper — I shot Mike an email to ask for his read. What follows is an expert interview that has been edited for clarity and length — the first, I hope, of many.

Royce Kurmelovs: I’ve noticed a tendency on the left side of politics in Australia to ignore the world of finance on the basis that it is mostly full of useless people and that bankers are greedy. I don’t necessarily think they are wrong about that, but I wanted to kick this off by asking you: why should any of us pay attention to what happens within the world of finance?

Mike Rafferty: I agree, there is a curious disdain for finance by lots of progressive folks that seems almost or actually moral in its impulse. Let’s be clear: we don’t want to extoll the virtues of finance, but we do want to say that some really important things are going on in and through finance that people should be paying attention to. To observe that finance is at the frontier of many of the most important and contradictory processes in our society is not a validation of what is happening. Rather it is an opening to explore those frontiers in search of opportunities for new social possibilities for resistance and transformation.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, activists and scholars rightly focussed on the emergence of the factory and mass production. Those looking to understand what was then happening recognised that they needed to pay attention to these developments in order to find ways of challenging exploitation, inequality and the social imposition of scarcity as a constitutive requirement of capitalism. So Marx studied the reports of factory inspectors (the Blue Books) and Engels did an amazing study of life and living conditions in Manchester. They were outraged at what they were finding and seeing, but they did not turn away from the field because they knew they were important and — for all their morally objectionable outcomes — they allowed us to rethink forms of resistance.

RK: You co-authored Risking Together with Dick Bryan about this process of risk-shifting. Can you briefly lay out what is risk, why it matters and how it is contributing to growing class inequalities?

MR: The book on risk shifting is part of a longer-term attempt to understand what has been developing in capitalism for the last three to four decades.

A crucial development that makes risk central to modern finance, and our daily lives, is that finance — as a frontier form of capital — has found new ways of accessing our lives in and beyond the workplace. It has been able to do this because finance has developed a logic of thinking and acting for employers, firms and governments that allows things to be broken down into smaller components and activities, and these bits re-framed as “risks”. These risks can then be priced and — crucially for finance — the cost can then be shifted onto someone else. And just as in the labour market where workers are formally equal to employers but face a structural inequality, as a class we have all been made into risk traders but find ourselves sitting ducks in the financial world as every institution we interact with has more resources and expertise.

Partly because of the inherent asymmetry of households in the world of risk trading, capital has opened up a large new way to generate profits from us in more and more aspects of our daily life, from our workplaces to the household budget — to even monetising our social lives.

“These risks can then be priced and — crucially for finance — the cost can then be shifted onto someone else.”

At work, for example, we know that there has been a growth of platform-based jobs like Uber and Airtasker. We know these jobs as precarious, but the financial logic that drives them is that these platforms unbundle the employment relationship and shift the risks of benefits like sickness and annual leave back to the worker. In other words, the worker is carrying all the costs of getting sick. Similarly, the state is stepping away from its responsibility for funding retirement through compulsory savings like superannuation. And those savings are in turn managed by financial intuitions who don’t have to guarantee retirement security, but still clip the fees on your savings while exposing us to financial market volatility.

Then there’s household bills. When you contract with a utility provider, you sign a virtual financial contract to pay for certain services for a fixed period. The terms of that contract and options are priced with financial precision to guarantee a return to the firm. Even the credit checks that utility firms conduct on you for your phone plan or power provision are the same as if you were taking out a personal loan.

RK: A couple of weeks back in Raising Hell, I reported on the events of a senate committee hearing where representatives of the four biggest insurers in the country admitted they had done nothing about climate change. What’s your read on that situation?

MR: In Australia and the US in particular, business lobby groups have pushed back against moves by governments, citizens and even other businesses to grapple with climate change. In Australia, the Minerals Council played a key role in resisting efforts to reduce carbon emissions, because they saw it as a threat to the viability of their current and future coal projects. Their political allies at the time launched an unrelenting misinformation and scare campaign that showed just how powerful big business is when it flexes its muscles.

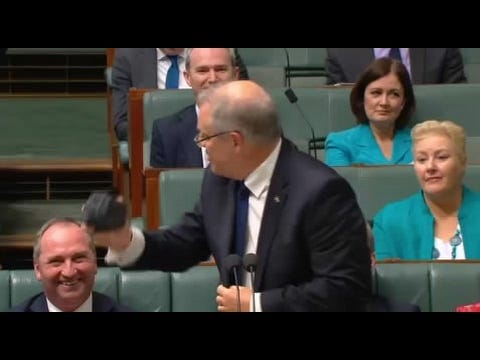

Not all business groups went along, and of course many civil society groups spoke out against the cynical fear mongering, but they were no match against this coal loving coalition — remember the theatre of our current PM bringing a lump of coal into House of Reps and you know how crazy that campaign was.

Interestingly, in recent times, the two big global mining conglomerates, BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto have distanced themselves from the Minerals Council’s earlier hard-line anti-climate change position, and even announced plans to move toward carbon abatement. While this is to be welcome ethically, the hard financial reality is that many environmentally damaging projects may become either worthless or could not be sold — they’re called stranded assets — should global emission standards catch up with what the science says is needed.

But it is because the insurance industry is being forced to price the risks and costs of environmental change that the urgency for some form of action may come through. We know that many banks have signed up to climate change agreements, which means they are committed not to fund new projects that will have adverse effects on the climate. Insurance companies too, which use inter-insurance company arrangements to share risks via re-insurance markets, are realising that many of these risks are so profound and costly that they may not be able to price them. These risks may increasingly be simply uninsurable.

RK: Do you also think it is insane the people whose job it is to manage risk seem to have little to say and have not organised to respond to climate change?

MR: Yes, sort of. Insurance has sort of been passive form of finance. It has cast its role largely in pricing and trading event risks. And it has done very well thanks very much to the growing markets for more and more types of insurance. So it has no real need to step up and become active in changing the development of risks from climate change. But that phase may be coming to an end. Just like car insurance where risk analysis looks not just at overall accident statistics but individual behaviours, it seems that climate change risks will be priced by industry and even firm behaviour. It may well be that in order to get more certainty in pricing future event risks associated with climate change, the industry may need to be more active in climate change abatement. We can see some signs of this already, but its early days.

RK: How much of our inaction on climate change can be read as another dimension of this broader process of risk-shifting? And what makes it different to the past?

MR: I think there is a certain financial logic in play here, yes. In finance, the logic goes that in order to take on more risk there needs to be adequate compensation – the risk-reward trade-off. But the holy grail of finance is where a firm can make a profit without taking on any risk — it’s called arbitrage. If a firm can shift risk and still get the reward it still can make arbitrage profits. This is meant to be a minor activity because financial markets are assumed to be efficient and all players equal. But as we know, households enter financial markets with very limited ability to shift their risks, and are perfectly positioned to have to absorb them. So financial markets have found an enormous risk transfer arbitrage gold mine in the average household.

“Because they are profiting from deteriorating conditions, they are effectively betting against those who are seeking to slow or reverse human induced climate change.”

This notion that profit can be made without taking on risk, or that risks can be shifted, helped produce the sub-prime meltdown in 2008 and has extended into the business world more broadly. Arbitrage works also with regulations — so in tax law, firms can nominate countries or tax categories where they can pay little or no tax, and in this way firms can arbitrage country tax codes. With environmental regulation too, firms can not only locate activities where they do not pay for their environmental damage, they can even lobby to change regulations to achieve the same result.

RK: To close this off, does the failure to take into account the risks from climate change mean the insurance industry is effectively shorting our interests?

MR: Yes, to use another financial term, if the insurance industry simply continues to take the view that its only role is to price event risk, they are accepting that climate change will get worse, and because they are profiting from deteriorating conditions, they are effectively betting against those who are seeking to slow or reverse human induced climate change. That can be thought of as shorting the global climate, because in this way insurance profits from things getting worse.

Before You Go (Go)…

If you’re lurking and like what you see, throw me a subscription to get my screeds straight to your inbox every second Tuesday — it’s free. If you like what I do and want to see me do more of it, throw me a paid subscription — it’s $5 a month or $50 a year. Are you skint? Or flush? Well, you can also pay what you feel I’m worth by setting your own yearly rate.

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, or leaving a review or just tell a friend about Raising Hell!